(Best viewed with screen resolution set at 1024 x 768 pixels)

"To the Uttermost"

Captain B.W.L. Nicholson RN, CBE, DSO

First Headmaster of the Prince of Wales School,

1931-1937

Captain B.W.L. Nicholson, 1879-1958

Courtesy of Cynthia (née Astley) and Alastair McCrae

Introduction

When it came to blazers, we Princeo chaps had a distinct advantage over our Yorkist rivals: which Boma or

Convent girl would not favour gold braid on navy blue over silver on maroon? Rumour had it that we had our first

headmaster, Captain Nicholson to thank for this, for it was he who had introduced the colours of the Senior Service to a

school 6000 feet above sea-level.

Six days a week did we worship the Lord in the assembly hall, and in later years in the chapel. But on

the seventh day, Saturday, Sir Herbert Baker’s colonnades came into their own. Boys who were normally required to traverse

the quad were ranged around in the shade to witness the Flag Parade ceremony, where the Bugle Band did its bit and a school

prefect did the honours. Again, we heard, this was a carry-over from Dartmouth Royal Naval College.

Yet Nicholson was a largely unknown character – at least for those of us who were at school in

the ‘fifties and later. It is true that a boarding house named after him was located somewhere in the Wild West of the

compound, but no headmasterly portrait of him gazed benevolently from the library walls. Having retired in England, he

did not grace sports days or Queen’s Day in the guise of the wise mzee.

The truth is that Captain Bertram W.L. Nicholson was no ordinary schoolmaster. He had not swotted his

way through grammar school, nor was he familiar with the playing fields of Eton. He had not punted along the Cam or

debated at the Oxford Union, nor had he prepared pupils for matriculation. He was a naval officer, used to leading and

dealing with all sorts and conditions of men. Perhaps this was the reason for his appointment to Kenya in 1925, where

he would be expected to deal with the sons of settlers, officials, voortrekkers, technicians, merchants, missionaries and

remittance men. That he was successful is proved by the fact that the school of which he was the first headmaster

came to be recognized by the Colonial Office as "the most important European school in British colonial Africa" (CO 1045/110)

and remains to this day, as the Nairobi School, one of the most prominent schools in Kenya.

There is surely no time like the present to discover a bit more about our founding headmaster, where on

the one hand OCs around the globe can pool their resources at the click of a mouse, and on the other there are some

veterans who actually knew him still around to help us tell the tale.

The Family Background of Bertram W.L. Nicholson

He "moves in the best society", noted Captain Pilcher on the naval service record of Commander

Bertram William Lothian Nicholson (hereinafter, Bertram) in April of 1919. It is hardly surprising, given his family

background. Like so many Dissenters

(http://www.victorianweb.org/religion/dissntrs.html), to whom military and other

careers were foreclosed, by the early nineteenth century the Nicholsons, originally from Oswaldkirk in Cumberland,

were successful and wealthy London merchants with a haberdashery business in what is now Gresham Street. Worshipping

at the Essex Street Unitarian Chapel, they rubbed shoulders with many of the leaders of business and society,

including Bertram’s grandfather’s distinguished father-in-law, William Smith, heir to an extensive wholesale grocery

business and noted for his energy in promoting Abolition and Parliamentary Reform. As a Member of Parliament and

Fellow of the Royal Society, William Smith counted among his friends and house guests such men as Charles James Fox,

Joseph Priestly and William Wilberforce, and the distinguished political economists Malthus and Ricardo.

Waverley Abbey, Seat of George Thomas Nicholson, Esq. engraved by

H. Adlard after a picture by T. Allom. Published in A Topographical

History of Surrey, 1850. (Image courtesy of antiqueprints.com)

In the early nineteenth century, Bertram’s grandfather, George Thomas Nicholson, acquired the

elegant country estate of Waverley Abbey House and lived the life of a country gentleman. House parties and visiting

were important aspects of life. Florence Nightingale, a niece, was among the frequent guests, opening up other

avenues of social contact and on at least one occasion, George and his wife slept 80 guests. Although he did not

himself pursue a political career, he demonstrated his commitment to liberalism by his financial contributions to

the electoral campaigns of his father in law. The family could hardly have foreseen that the repeal of the Test Act

in 1828, the campaign for which was led by William Smith, would open the way to notable military careers for so many

of his descendants. (The Test Act’s repeal ended the Anglicans’ monopoly of public office.)

George’s wife, Anne, gave birth to four sons and two daughters. Of the latter, Laura married

into the prominent Bonham Carter family and Marianne married Douglas Strutt Galton; a later generation of Galtons

married into the Italian Fenzi family – is anyone now recalling the Galton-Fenzi memorial near the post office at

the end of Kenyatta Avenue, Nairobi? Of the sons, Samuel inherited the Waverley estate and established a brewery

in Maidenhead, later subsumed under the Courage label; George, whose marriage proposal to Florence Nightingale had

been rejected, later drowned in Spain; William married the daughter of a knighted vicar and became a captain in the

26th foot (Cameronians). One of William’s sons was to become Admiral Sir Stuart Nicholson.

The remaining son, Lothian, Bertram’s father, enrolled with the Royal Engineers. Among his

various postings, Lothian was responsible for the destruction of the Sebastopol Dockyards following the Crimean

war and contributed his bridge-building skills to the relief of Lucknow. In the 1860s he married the Hon. Mary Romilly,

daughter of Sir John (and later Baron) Romilly, the distinguished Parliamentarian and legal reformer, who at varying

times held the positions of Solicitor General, Attorney General and Master of the Rolls.

(The picture at right of Bertram’s father, General Sir Lothian Nicholson, KCB, RE, is from a private collection.

It was discovered by Suzanne Le Feuvre.)

There were three daughters and seven sons from this marriage. Of the sons, three joined

the army and rose to the rank of Major General; two of these were knighted and the third, whose main career was

with the Indian army, was ADC to HM King George V for a brief period. Two followed their cousin, Admiral Sir

Stewart Nicholson and joined the navy, as did their cousin Commander Francis Romilly, one of the first casualties

at the Battle of Majuba Hill (“speared through the spokes” as one account expresses it). Douglas served for a time

as Commodore of the royal yachts and ADC to the King in 1913-14, later became an admiral and was knighted. Bertram,

the subject of our interest, rose to the rank of Captain and would likely have also attained flag rank had it not

been for his voluntary retirement at the time of naval retrenchment in 1922.

The birthplaces of Lothian’s children reflect the mobility of their father – London, Gibraltar, Ireland and Jersey,

where Bertram was born in 1879, during his father’s tenure as Lieutenant Governor. Following this assignment,

Bertram’s father served as Inspector-General of Fortifications and Engineers; he was knighted in 1888; and in 1891

he was appointed Governor and CinC Gibraltar, at which posting he died of malaria in 1893.

Few families can count among their ranks one generation of such talent and distinction.

Even discounting the prominence of members of the wider family, Bertram Nicholson could hardly have moved in less

than the best circles. It is as though the family had adopted as their ethic the admonishment of their great

grandfather, William Smith, to fellow advocates of Parliamentary Reform at the Crown and Anchor in 1809:

“(You have three enemies:) To corruption, oppose integrity and vigilance; to prejudice, moderation and calm

reasoning; to apathy, zeal and activity; but above all, be fortified with patience to withstand disappointment,

and with perseverance to maintain the struggle.” (Richard Davis, Dissent in Politics, 1770-1830: the political

life of William Smith, MP, London, 1971, p.141.)

Bertram Nicholson’s Naval career, 1893 – 1922

He is “an officer and a gentleman of high, indeed lofty, ideals.” So wrote Vice Admiral

(later, Admiral of the Fleet) Sir John de Robeck in 1918. Bertram W.L. Nicholson – for present purposes let’s call

him by his Prince of Wales School name, Nick – entered the service on July 15, 1893, barely six weeks following his

14th birthday and three weeks after the death of his father. He attained the rank of Midshipman on 18 November, 1896

and was promoted Lieutenant on 31st August, 1901, Commander on 31st December 1913 and Captain on 30th June 1919.

(In this picture, courtesy of Britannia Royal Naval College, BWL Nicholson stands at left as a lieutenant at

the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth sometime between 1908 and 1910.)

After entering the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth in 1893 and training as a Cadet on the hulk

Britannia, Nick’s first postings as a Midshipman were to the battleship HMS Ramillies in 1896, followed by the brand-new

HMS Diadem on her completion in July of 1898. That he was subsequently appointed as an instructor to the staff of

the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth 1908-1910, perhaps suggests an early interest in education; more importantly,

it reflects the judgement of those who mattered that he was of a calibre to be trusted with the important role of a

training officer at what was then the equivalent of a specialized public school. He must have had a talent in that

direction, for in March of 1914, his record noted “Strongly recommend for training service.” Of course, Europe was

still at peace in March of that year.

HMS Cressy, ca. 1907-08: upon which Nicholson was Executive Officer and 2i/c

(Courtesy Kosaku Ariga (Jarek),

http://www.warship.get.net.pl)

The First World War began badly for Nick. Following a War Staff course, he had been posted as 2 i/c

and Executive Officer aboard HMS Cressy on April 9, 1913. On September 22, 1914, and in the space of less than an hour,

the outmoded cruisers HMS Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy were all torpedoed and sunk off the Dutch coast. Various figures

have been seen regarding the numbers of lost and survivors. The Admiralty announced 839 survivors shortly after the

event and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission records list 1448 memorials of men from the three cruisers.

“About a quarter of an hour after the first torpedo had hit,” reported Nick, “a third torpedo, fired from a submarine

just before starboard beam, hit us in No. 5 boiler-room - time 7.30 a.m. The ship then began to heel rapidly, and

finally turned keel up, remaining so for about twenty minutes before she finally sank at 7.55 a.m.” Cressy’s own boats

were already full of survivors and so it is not surprising that she suffered the greatest number of men

lost (562, including her Captain and 21 other officers out of a complement of 766).Nicholson is believed to have been

among the 156 men plucked from the water by the Lowestoft trawler Coriander.

(Reports on the incident by Nick and Commander Norton of the Hogue may be found at URL,

http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/cressycommander.htm.

There is a link to Kapitanleutenant Weddigen’s report.)

The victor was the German submarine U9, commanded by Kapitanleutenant Otto Weddigen. Weddigen

and his crew became instant national heroes. Apart from the award of Iron Crosses to every crew member, a memorial

medal was struck. (One of the latter was sold on e-Bay in October 2005 for £21.)

The Weddigen medal

Credit: transient image posted on eBay

U9 had another small place in maritime history as the first submarine to reload torpedoes while

submerged. She survived the war, but Weddigen was not so fortunate. He was lost with all hands aboard U29 when she was

rammed in the Pentland Firth by HMS Dreadnought in March 1915.

Weddigen and his U9 may have one other claim to notice in the history of our school. Three

weeks after the loss of the three cruisers, U9 attacked and sank HMS Hawke. It would not be surprising if this was on

his mind when Nick was selecting House names and latched onto Admiral Hawke, who has been called the father of the

modern British Navy.

The success of this U9 attack brought home to the admiralty the full dangers of submarine attack,

which they had previously been inclined to discount. Within days of the tragic loss of the cruisers, Nick was posted to

HMS Iron Duke, Jellicoe’s Flagship, as “additional for command of Flotilla of Armed Trawlers”. In other words, he was

additional to normal strength on Iron Duke. The position has not been closely investigated, but it looks as though this

was part of the response to the sudden realisation of the fleet’s vulnerability to submarine attack. Nick probably was

aboard one of these armed trawlers, rather than Iron Duke itself. This flotilla was known as the Northern Patrol,

which he commanded until November of 1915 and for service with which he was specially commended in January of 1916.

It was the start of an anti-submarine role which, in its various dimensions, was to be repeated during the rest of

Nick’s service in both world wars. These trawlers had a variety of functions, including mine sweeping and mine laying,

but their main use was in anti-submarine duties and fleet protection. Particularly in WWII, many of these were custom

built to Admiralty designs and were not commandeered or rented vessels – yes, the Admiralty did sometimes pay rental fees!

Nick presumably then had some leave, for his marriage took place in October of 1915, postponed

from an original date in April for the call of duty, no doubt! His County Down bride was Evelyn Douglas Montague Browne,

daughter of Major General Andrew Smythe Montague Browne, sometime Colonel of the 3rd Dragoons and the Royal Scots Greys.

In fact, she was his sister-in-law, his brother Octavius having married her sister Eileen in 1911.

Following this, and no doubt reflecting his growing reputation as an excellent organiser, Nick

was placed in command of HMS Zaria, sometimes described as an “Armed Merchant Cruiser”, although in fact it was a depot

ship of 3500 tons, based at Longhope, Orkney. It is not known whether it serviced its subordinate vessels, whose crews

would have been listed as “Zaria”, in harbour or at sea. The battleship HMS Orion, to which he was posted as Executive

Officer in March of 1917, was Nick’s last wartime posting.

While details of this period in Nick’s life are relatively scant, his service was considered

highly satisfactory by his superiors. His record is littered with remarks enough to gratify any man: “excellent officer”,

“marked ability”, “good organiser”, “most loyal and zealous”, “VG cricketer”, “keen hunter”, “excellent work”, “ever

keen on the hunt for enemy submarines”, “acted with great promptitude”, “most energetic and excellent executive officer”,

“strong sense of duty”, “strong will”, “v.g. disciplinarian”, “keeps himself very fit physically”, “plays all games”,

“in all respects is a most capable officer”. Additionally, in June of 1917, he and another were awarded the DSO “in

recognition of their services in vessels of the Auxiliary Patrol between the 1st February and 31st December, 1916.”

His war service was not entirely lacking in events which might have brought criticism. He was

involved in two courts of inquiry, one involving a foundering of one of his trawlers and one a stranding. He came

through these with expressions of approval. On one occasion only was a reprimand placed on his record with respect to

the grounding of the Venetia: “informed by the Admiral that in view of weather conditions it was an error in judgement

to enter Mill Bay (in the Orkneys) at as high a speed as 9 knots”. It is hard not to smile, and indeed the service did

smile on him.

The last notation on his WWI record which had any bearing on his personal conduct and character

was from the previously quoted Captain Pilcher, just months before Nick’s promotion to Captain: “Specially recommended

for advancement. I consider this officer’s attainments of a very high order. Possesses a very high sense of duty and

principles which he exercises in himself and exacts them from others. Generally well read. Should attain distinction

in the higher ranks.”

The Nicholson brothers in an undated photograph taken some time prior to March of 1933.

Standing, from the right: Captain Bertram Nicholson (b.1879), General Octavius Nicholson (b.1877),

Major-General Sir Francis Nicholson (b.1884), George Nicholson, a Civil Engineer (b.1871).

Seated, from the right: Charles Nicholson, a Lawyer (b.1868), Major-General Sir Cecil Nicholson

(b.1865, d. March 1933), and Vice-Admiral Sir Douglas Nicholson (b.1867)

Note: Charles does not appear in the genealogy from which family information was derived for this

article and may be a cousin. Brother John (b. about 1876, d.1932) is missing from this photo.

(Courtesy of Michael John Lothian Nicholson)

Foreshadowing his subsequent classroom role at the Prince of Wales School, Nick had taken a

French exam in 1919, and in 1920 he attended a one-month course “to re-qualify as French Interpreter.” In May, he was

appointed under the Director of Naval Intelligence to serve as interpreter to “the Danube Conference.” The next year

was spent in Paris and his service with D.N.I. terminated on July 24, 1921. For June 1921, the record notes “F.O.

(Foreign Office) express thanks for Capt. N’s services in connection with work of Danube Conference.” He attended a

Technical Course from October 1921 and a War Course from March 1922. The last entry in his record reads “Retired at

own request – 14:7:22”.

Although Nick had retired voluntarily, it was done in the context of a planned reduction in

naval strength. It is to be expected, therefore, that this was a considerable disappointment since only three years

earlier it appears he had been marked for greater things in the Royal Navy.

Nicholson and the Nairobi European School

Three years after resigning from the Royal Navy, Nicholson charted a new career course and set

sail for Kenya in 1925. How his name came up as a candidate for the headmastership of a planned, major secondary

school in the Colony is unclear. That he knew people in high places and moved in the best circles had already been

noted by his wartime naval superiors; it has been suggested, moreover, that Mrs. Nicholson’s family may have been

connected to that of Kenya’s Governor, Sir Edward Grigg. Whatever the case, as we said at the beginning of this

feature, the position to which Bertram Nicholson was appointed was a challenging one and he was seen as the right

man for the job.

The Kenya to which Captain and Mrs. Nicholson came in 1925 was a thriving, turbulent British

Colony in which the European population had doubled and then trebled in the years following the First World War.

Politics and society still resembled those of a frontier territory where the rules of the old country seemed not to

apply – a recent example of which was a hare-brained settler plot in 1922 to detain the Governor as a hostage and

thereby force the Colonial Office to grant self-rule to whites. In opposition to the settlers’ ambitions, Kenya Asians,

led by A.M. Jeevanjee and Manilal Desai and strongly supported by nationalists in India, pressed for equal rights with

Europeans. African opposition was represented by Harry Thuku and the East Africa Native Association in a series of

mass meetings across Central and Nyanza Provinces to protest unfair land and labour laws. Caught in the crossfire,

the British Government settled the matter

in 1923 by declaring that Kenya’s future belonged to its African peoples and that the interests of the Africans must

be held paramount. For many years to come, however, that declaration was more rhetoric than reality (in spite of the

significant advances in developing African education that occurred during the twenties and thirties) because the white

settlers, led by Lord Delamere, continued passionately to assert a leading role for Europeans in developing the colony

for the betterment of all races. To preserve that role and provide for the grooming of future leaders, Delamere pushed

hard for better European schools, better teachers and, above all, better headmasters.

A special commemorative edition of the Impala notes that “in the early twenties a magnificent site

had been selected by Lord Delamere and the then Colonial Secretary, Sir Edward Denham, for the school that the most

far-sighted of Kenya’s leaders knew must one day be created. ...... When in 1925 Lord Delamere, with his usual

forcefulness, was urging the expenditure of a large sum of money on a new school for boys, he was opposed by no less an

authority than the Director of Education on the grounds that there would never be enough boys to fill it. Delamere

retorted that in two years there would be a waiting list. However it was to the vigour of the Governor, Sir Edward Grigg,

that the final decision was due. Although at the time he was much criticised for the alleged grandeur and extravagance of

the buildings that shortly rose at Kabete, Sir Edward was adamant. He defended the ‘provision of spacious public buildings

designed with grace and dignity.’ Such examples of architecture, he said, were an inspiration to a young country, a tribute

to the faith and vision of those who were building its future, and an inspiration also to its youth of every race.”

(From an editorial article entitled ‘Retrospect’ in the June 1952 Impala.)

It was an idea whose time had come. Christine Nicholls, in her book Red Strangers: The White

Tribe of Kenya (2005), records that in 1925, the provision of education for European children in Nairobi was at a low

ebb. The sole government school, Nairobi European School, consisted of unsatisfactory classrooms located in the former

European police barracks on Nairobi Hill and boarding blocks located near Buller Camp. So poor were the school’s

academic results that year compared with those of Indian pupils, that they were suppressed. In 1925, Sir Edward Grigg,

took prompt action. On the recommendation of Kenya’s Colonial (Chief) Secretary, Sir Edward Denham, Captain Bertram

Nicholson was appointed Headmaster of the Nairobi European School. It was a post Nicholson would hold for six years

while waiting for the proposed boys’ secondary school to open at Kabete.

The old Nairobi European School was an unprepossessing facility for Nicholson’s first

educational command. But in keeping with the government’s current commitment to improving education in Kenya,

twenty-five acres of land on the Hill were allocated for new buildings. The architect, Sir Herbert Baker, drew up the

design, and in 1928 a fine set of spacious new buildings was ready for occupation.

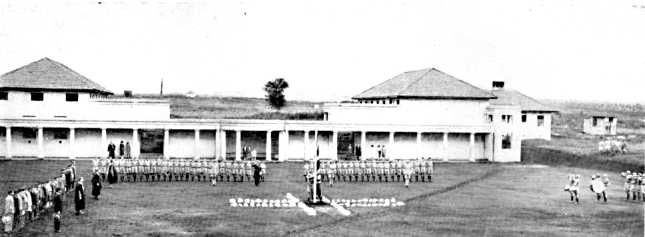

New buildings of the Nairobi European School designed by Sir Herbert Baker

(East African Annual, 1931-32)

Nicholson started as he was to continue. In 1927, the confidential report on Nicholson

submitted to the Colonial Office states: “B.W.L. Nicholson. Headmaster, Nairobi School. Very successful and fully

justifies his appointment.” (Public Records Office, Kew, file CO533/371/3 entitled Annual Confidential Reports 1927.)

A similar retrospective assessment appears in the June 1952 Impala where the Editor, M.A. Crouch, stated that

“Although a professional officer with a long and distinguished naval career behind him rather than a schoolmaster,

Captain B.W.L. Nicholson, DSO, proved himself a skilled administrator, a dynamic leader and, in spite of his own

modesty on the point, a teacher of no little merit.”

Nicholson’s headmastership at the Nairobi European School was not entirely free of controversy,

witness the religious and jingoistic slogans that he selected to be painted around the wall of the first floor gymnasium,

also used as an assembly hall. One was “O God help me to win. But if in thy inscrutable wisdom thou willest me not

to win, O God, make me a good loser,” and another was “Love of England, gratitude to one’s country, is the happy duty

of us all.” Their existence came to the attention of Professor Julian Huxley, who in 1929 was touring East Africa

on a mission to “report on certain aspects of native education” for the Colonial Office Committee on Native Education.

Huxley recalls in his book, Africa View, published in 1931, that the first quotation seemed “to embody a rather

out-of-date view of the Almighty and a wholly out-of-date view of educational aims.” The second, he notes, attracted

the ire of local Scots who were not to be appeased: they protested to Captain Nicholson, to the Director of Education

(who was Huxley’s host), to the East African Standard and, when Huxley departed, they were threatening to take the matter

to the Secretary of State for the Colonies.

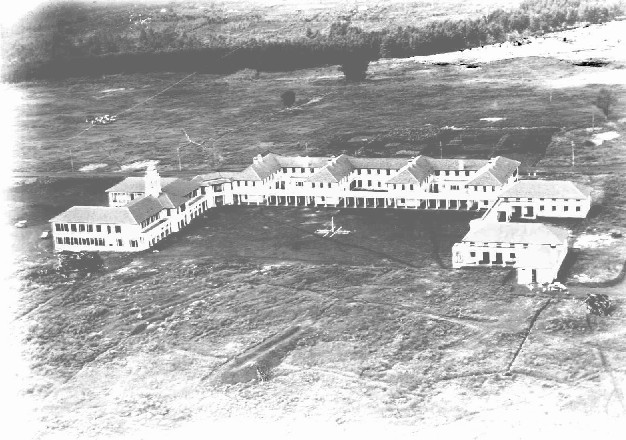

Construction of the new boys’ school at Kabete in 1930

(Courtesy of Cynthia (née Astley) and Alastair McCrae)

Nicholson had more important things to occupy his mind than a few angry Scots with a breeze up their

kilts. He was hard at work planning and preparing to run the proposed major new boys’ secondary school at Kabete.

During the six years that followed his appointment to the Nairobi European School, “he began to create the routine and

the tradition which he wished to take with him to Kabete when the new school should be ready. One of his early changes

was to introduce the House system; the three houses into which the School was divided were named after three great

figures in British history - Clive, Hawke and Rhodes – who seemed to him in various ways to demonstrate those British

qualities which he so much admired himself—courage, loyalty, and an abiding sense of duty. … During those six years

Captain Nicholson also began gathering his staff for the school at Kabete.” (Impala, 1952.)

The Original Staff in May 1931: Seated: Captain Nicholson centre; Bernard Astley 2nd from right.

Standing: Ray Barton 2nd from left, Jack Forrest centre, Cyril Redhead, and James Gillett at right.

The ladies at each end of the bench are Matrons; the lady standing is Captain Nicholson’s Secretary.

(Courtesy of Cynthia (née Astley) and Alastair McCrae)

The new school was by far the government’s most ambitious (and expensive) educational project of the era. Governor

Grigg had chosen the renowned imperial architect, Sir Herbert Baker, to design the buildings; Baker turned to Thomas

Jefferson’s Academical Village at the University of Virginia as the inspiration for this, his pièce-de-resistance

among Kenya schools.

(Please see article in this web site "Sir Herbert Baker and the Prince of Wales School").

And, to ensure that the school would be run on English Public School

lines, Nicholson’s own Dartmouth College and Sir Edward Grigg’s Winchester College were selected as the models for

discipline and tradition. To command a school of this calibre was a challenge worthy of a man such as Captain Nicholson.

He saw it as a means of serving and promoting the interests, not just of Kenya, but of the British Empire itself;

as history would show, it was his greatest and most enduring achievement.

Assuming Command of the Prince of Wales School

With six hundred acres of land south of the railway having been allocated as far back as 1922,

construction was undertaken by the Nairobi firms of Messrs. George Blowers and Messrs. Jacobson Bros. under the

architectural supervision of Sir Herbert Baker’s assistant, Jan Hoogterp. “On 24th September, 1929 Sir Edward Grigg

laid the foundation stone, sealing under it that day’s edition of the East African Standard and a current set of the

coins of the Colony. Unlike so many foundation stones it was not built into a wall, but took the form of a slab,

with an inscription in bronze lettering, set in the pavement below the clock-tower, a place so prominent that thousands

of feet must cross it daily in term time and no schoolboy can possibly fail in the course of his school years to read

its wording and thus be reminded of the Governor to whom more than to any other single person the existence of the School

is due.” (Impala, 1952.) And it should be pointed out that of all the Colony’s Baker-designed schools, the one at Kabete

enjoyed the finest site, commanding a magnificent view of Mt. Kenya to the north and Kilimanjaro to the south-east.

The Prince of Wales School, initially known as the Kabete Boys Secondary School, in 1931

(From the June 1952 twenty-first anniversary edition of The Impala)

On Tuesday 20th January 1931, the Kabete Boys’ Secondary School was launched with Captain Nicholson

at the helm and a crew of seven staff, eighty-four boarders, and twenty dayboys. The older boys had moved over from

the Nairobi European School, leaving behind the girls and the younger boys. In time, the Nairobi European School

would become known as the Nairobi Primary School, with the Kenya Girls School occupying some of its buildings until

the older girls moved to their own separate High School at Kileleshwa in 1951.

The grounds at Kabete were far from being developed and there were piles of builders’ rubble

all around. Unlike the dense canopy of original trees that had covered it as recently as 1900, Kabete in 1931 was an

open, grassy plain save for a few sacred wild fig trees. It must be acknowledged, however, that during the years of

waiting and planning at the Nairobi European School, Mrs. Nicholson, a talented and enthusiastic gardener, had been

joined by the Rev. Jimmy Gillett and members of the Scouts in making a start on the gardens at Kabete; some trees had

been planted, including an acorn from Gillett’s home in Sussex which by 1952 had grown into a fifteen foot oak in front

of Scott House. But no playing fields existed. “It was unfortunate,” wrote Mr. Bernard Astley, Science Master at the

new School, “that 1931 and 1932 were years of drought and locusts, so it was very difficult to get the grounds in order.

To make matters worse the specifications for the levelling of the main playing fields did not provide for the return of

the top-soil and it took nearly ten years to get a good grass cover on that part of the field nearest the tuition block

and in the main quad. To start with, we played games in the show ring of the Royal Agricultural Society’s adjacent

Showground—the site of the present Military Hospital.” (Quoted in the 1952 Impala.)

Much of the burden of labour was assumed by the school itself. Every afternoon after the move,

the lads were press-ganged (without a daily ration of grog) into working parties to lay out the sports fields; nor were

Masters exempted from wielding a jembe (a heavy, broad-bladed hoe), and no one worked harder than Captain Nick himself.

In addition to the shortage of playing fields, money for educational supplies was tight at the

outset. Mr. Astley recorded in his diary that “My main headache was equipment for the new science laboratories at Kabete.

The apparatus & chemicals at the Nairobi School had to be retained for the girls’ secondary school. Kenya had entered

one of its not-infrequent financial crises and little money was available. I prepared indents for the Crown Agents but

was instructed by the Education Department to reduce them by more than half and to improvise the rest locally!

Several years elapsed before we were able to equip the two laboratories to a modest standard. This was typical of

economies which had to be made by all Government Departments – Public Works, Medical, Forestry and so on. In fact

from the financial aspect the school could not have opened at a worse time and the most niggling of economies had to be

practised. However, it was useful experience for the war-time economies to come when every square centimetre of exercise

books and loose paper had to be written on – margins and covers as well” (Diary extract courtesy of Cynthia (née Astley)

and Alastair McCrae.)

The first Empire Day ceremony in the Quad, May 1931.

(Impala 21st anniversary edition, June 1952)

The first Empire Day Service, albeit a modest affair compared to subsequent celebrations, was held

in the Quad on May 24 1931. Another notable event in the first year was a change in the school’s name. On January 10

1931, Kenya sent an official telegram to the Colonial Office asking that HRH the Prince of Wales be sounded out about

using his royal title as a new name for the school at Kabete. Captain Nicholson, who had thought all along that ‘Kabete

Boys’ Secondary School’ was too clumsy, followed up with a letter to the Director of Education on February 3 1931 in

support of the name change. Nick’s first thought was that it should be the ‘Prince Edward’s School’; the Director,

Herbert Scott, suggested that the ‘Prince of Wales School’ would be a better choice. Nick agreed. Although some civil

servants in London raised the objection that a Prince of Wales school or college already existed in the Gold Coast, a

letter was issued by St. James’ Palace granting the Royal consent. (Name change details courtesy of Peter Liversidge,

Scott, 1957-61, from his own research at the National Archives in Kew.)

As a special case, consent was also given for a new blazer badge with plumed ostrich feathers,

set in a crown and placed between the horns of an Impala. The badge’s motto, a reflection of Nick’s personality and drive,

reads “To the Uttermost.” (In heraldic tradition, ostrich feathers symbolize willing obedience and serenity. Set in a

crown, they have graced the coat of arms of every successive royal Prince of Wales since the time of Edward the Black

Prince in 1343.)

In turn, the new school name and badge begat a complementary new blazer. Gone was the grey

carry-over blazer from the Nairobi European School with its lion

rampant badge;

in its place was a Senior Service dark navy blazer with gold braiding around the lapels, collar and hem, across the

top of each lower pocket, and around each sleeve in a band three inches above the cuff. For prefects, the gold

braid around the left sleeve was extended in an upwards crisscross to form a diamond similar to that worn by cadets

at HMS Britannia where Nick had trained in 1893. (The Prince of Wales prefect’s faded emblem shown at right above

includes a School Prefect’s crown; in this particular example, the crown’s red backing indicates that the wearer was

also Head of School.)

A Snapshot of the Prince of Wales School in 1932

That Captain Nicholson had things pretty much shipshape by 1932, is the strong impression one

gets from reading Volume 2 of that year’s school magazine. Unfortunately this particular edition is the only one

covering the Nicholson years that is currently available to the

Impala Project, but we found it to be to be a

fascinating and illustrative window onto life at school with Captain Nick on the bridge. What follows is a select

digest of information and quotations from The Impala, Volume 2 of November 1932.

Captain B.W. L. Nicholson in 1931

(Courtesy of Cynthia (née Astley) and Alastair McCrae)

We learned for example that since the first Impala was published in January 1932, the School had

shown ever-increasing signs of virile growth and that the last two terms’ achievements were a source of pride. The pass

rate for School Certificate was up over the previous year, and to those who failed a reminder was offered that “success

in examinations is not necessarily a guarantee of success in life, nor can failure be offered as trustworthy evidence of

lack of ability or intelligence.”

We also discovered that Mr. Bernard Astley (who succeeded Captain Nicholson as Headmaster in 1937)

went on leave in March and married Miss Barbara Sinton at St. Albans Abbey on 23rd July 1932; that Rhodes was Cock House

for the past two terms and showed more scholastic ability than the other houses; and that Hawke won the Davis cup for

Athletics, its first cup since the school opened. (The pre-existing Houses from the Nairobi School were Rhodes, Hawke,

and Clive. Grigg House, named after the Governor, was added as a dayboys’ house soon after the school opened at Kabete

in January 1931. It was later decided to discontinue the practice of putting day boys in a separate house, at which time

the name Grigg briefly fell into abeyance before being resurrected in 1948 when the new Hawke-Grigg boarding block was

completed. Nicholson House was added in 1944 in honour of its namesake and Scott house followed in 1948.)

Other bits of news included references to the school gardens which had continued to flourish

under the guidance and care of Mrs. Nicholson and the Rev. Gillett, and to the playing fields which were still brown

and bare from recurrent plagues of locusts. The Prince of Wales, it appears, was unable to repeat its previous year’s

victory over Nakuru School at rugby, but it won the Ruben Cup for inter-school boxing by defeating Nakuru by five fights

to two. During the first term of the year the school was kept in quarantine by mumps, and Prize Giving Day had to be

postponed until Empire Day; on that joint day, however, “prizes were presented by His Excellency the Governor, Sir

Joseph Byrne, K.B.E., who also presented new colours to the two Scout Troops. The occasion was also noteworthy for

the first appearance in public of the School Cadets (later to be known as the CCF), when His Excellency inspected the

Guard of Honour whose smartness and efficiency reflected great credit on the School and the Cadets’ Commanding Officer,

Captain Forrest.”

All of these events and activities occurred during the Great Depression: “Naturally our

activities have been somewhat handicapped by the essential economies following on the world-wide trade depression,

which Kenya has felt perhaps less acutely than many other countries, although it has suffered great loss through the

ravages of the locusts.”

The main objective of our research was however to seek out Captain Nicholson, and within the

magazine’s pages we did indeed find a hard-driving Headmaster who taught French, ran a killer cross-country race, played

scrum-half and wicket-keeper respectively on rugby and cricket teams, acted in school plays, salted his utterances with

nautical metaphors, and ran the school like a navy ship in which everyone on board, boy and Master alike, was expected

to do his duty “To the Uttermost”.

On Empire Day 1932, after a parade in the quad, the School’s distinguished guests,

parents, and staff moved to the dining room for lunch, prize-giving and speeches. Among the day’s guests were the

Governor of Kenya, Sir Edward Byrne, the Bishop of Mombasa, Rt. Rev. W.A. Pitt-Pitts, the Director of Education Mr. H.R. Scott, and the Reverend

J.F.G. Orr, Minister of St. Andrew’s Church. The Director of Education spoke first and set the tone by reading aloud

the Empire Day address of Nicholson’s old boss, Lord Jellicoe, Admiral of the Fleet, which exhorted the boys to think

imperially and work together for the good of the Empire as a whole.

Captain Nicholson responded in similar vein by recalling the vision of the school’s founders

and setting the School firmly in the context of the imperial vision. “Empire Day,” he said, “embodies in its meaning the

high purpose and tradition which must always inspire this School in all its actions and endeavours, for in the conception

of this School in Kenya must surely be found the determination to build up and solidify the further extension of our

Empire in this part of Africa. This School is indeed a monument to the considered opinion of the Government and the

people that we as a race have decided that we can make this our home where we can develop as other Colonies and Dominions

have developed. The School has been given perhaps the most beautiful position of any School in the world …. and it is to

those who loved Kenya best and who had the greatest faith in its future that we owe this site. One of those,

Lord Delamere, has been lost to us this year but his great interest in our welfare and his great faith and belief in

this country must ever be a source of inspiration to this School. To Sir Edward Grigg we owe the greatest debt of

gratitude for the energy with which be brought his conceptions as regards this School into vigorous action; he was

ever determined to see this School in being and I hope that no one will say that he was wrong.”

Captain Nicholson then went on to defend the decision to build so grand a school building at

Kabete during a time of world trade depression. “There have been criticisms put forward against the ornamentation and

elaboration of the building, but Sir Edward Grigg in asking Sir Herbert Baker to design the School was following a

natural human current of thought that in such a beautiful site nothing but what was really fitting to its surroundings

should be erected; and it would be difficult to find a building which is more efficiently designed to the tropics. Sir

Edward Grigg visualized a great future for this country and caused to be built what he hoped would become a great school.

Position and building have left us a legacy and an onerous one, the spirit of which I hope we are endeavouring to carry

out, for it is impossible to live in this place without a perpetual urge to make its surroundings beautiful. And if I

have been hard on the tasks of manual labour that I have set their sons in their playtime hours, I hope that the parents

will forgive me and take upon themselves the credit, justly due, that their sons are creating here a thing of beauty

which in time to come the Colony and the Empire may be proud of.”

Concerning enrolment and the capacity to meet demand, the Headmaster reported that “the School

opened in January 1931 with a roll of 83 boarders and a total of 112. At the commencement of this year owing to the

press of applications it was found necessary to utilize the verandahs for extra sleeping accommodation and we now have

100 boarders and a total roll of 140. This is a very considerable increase for one year but it is not anticipated that

the numbers will increase next year as I understand it is the intention of the Department that we should start at

Standard VI instead of Standard V, unless there is reasonable hope of a new boarding block which I am afraid is an

impossible prospect to look forward to.” (Captain Nicholson was referring to the effect of having brought primary

standards five through seven to Kabete from the Nairobi European School in 1931.)

Turning to academic progress, Captain Nicholson asserted that “there can be no two opinions

of the benefit of coming to Kabete: the first year’s work showed an improvement in the Examination results from 52 to

65 per cent. In 1930, at the Nairobi School, we entered 44 candidates out of which 23 were successful; in 1931 at

this School we entered 52 of which 34 were successful; and at the end of this year we expect to enter 62. I am happy

to be able to report that we had a much greater success in the final School Leaving Certificate than ever previously,

as five out of the seven candidates were successful. We hope that it may be found possible to form a class in 1933

which will be a post School Certificate Class and prepare for the Higher School Certificate or Intermediate.”

In other matters, “the general drive of the School shows much more activity and keenness.

You have seen, Sir, a sample of the Cadet Corps which are under the able guidance of Captain Forrest, to whom Your

Excellency has lately given a commission in the K.D.F. (Kenya Defence Force), and the Boy Scouts under Mr. Redhead

(and) I can assure you that the School is equipped with a Staff which is loyal to the bone and who devotes itself

whole-heartedly to the interests of the Boys in and out of School hours. I may indeed say that such things as Free

Periods are unknown at this School until bedtime.” (One of Nick’s more controversial rules was that boys and staff

alike had to be in bed with lights off by 10.00 pm. See below in the section on staff tributes following Nick’s

death in 1958.)

Captain Nicholson concluded by addressing a pet peeve. “I hope you will forgive me if I touch

on a point which is really between me and the parents though incidentally it concerns us all here. There can be no doubt

that we are going through a time of greatest strain and anxiety in the Colony and you, Sir, who are bearing the brunt of

the burden, have our implicit confidence that you will bring the ship into safe channels.” The issue was allocation of

funds: too much in his opinion was earmarked for “stodge” (food) and not enough for sports and equipment: “Jam has no

stimulating effect,” he claimed, “especially if taken in large quantities before playing football.” He was pulling no

punches: “The future of the Colony lies with the Boys of this School, and it is my ambition to see these boys filling

the Government and the Commercial Offices of this country. The future of the boys depends on the future of the School.

The future of this School rests very largely on the financial support it can receive, and by that I do not mean support

from the Government.” In this he was appealing for parental and community largesse. He wanted money for grounds and games

and trophies and prizes, all of which would create tradition and stimulate effort. He was speaking personally as an avid

fitness buff, a fiercely competitive player, and a fervent believer that leaders were formed on the playing fields of a

great school.

In his responding remarks, the Governor, Sir Edward Byrne, stated that “what has impressed me

most during my visits to Kabete is the manly spirit displayed by the boys and the strict but kindly discipline which is

enforced. I believe that these important attributes are largely due to your own personality, a personality based on the

fine traditions of the British Navy. I further venture to think that no small credit is also due to your good wife. We

have been most fortunate in securing your joint services during these early days of the School's life for the good

tradition you have founded will I am sure be carried on by your successors.” And for the lads, Sir Joseph Byrne had the

following message: “In conclusion I should like to impress upon you boys the importance of these few years when your

characters are being moulded. Most of you will probably settle in this country and those who have the interests of

Kenya at heart are keenly desirous of giving to her youth, regardless of race, the best possible chance of making good.

Therefore put your very best into it whether at work or at play.” He concluded by saying that “in so far as Kenya is

concerned 'work together' means friendly and effective cooperation between all sections of our community.” (A sentiment

echoed at Independence thirty-one years later by Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.)

The Director of Education, Mr. Scott, also had a message for the lads: “We of the generation

passing on admit that we have made a mess of the world. Well, we shall be prepared to say ‘Here you are. Carry on and

do it better!'”

The Prize Giving was concluded by the School Choir singing ' Land of Hope and Glory,' with

everybody joining in the chorus, the National Anthem and finally three cheers for His Excellency.

Elsewhere in the 1932 Volume 2 edition of the Impala Magazine there is much other fascinating material – not least of

which the essay on Kakamega’s gold rush by senior boy James Allen Edwards predicting a new Johannesburg for Nyanza

Province, and another by the Rev. Jimmy Gillett describing his eight-day flight from Kisumu to Croydon aerodrome in

England – but our focus continued to be on Captain Nicholson. We found him mentioned again in connection with school

plays, and within the blow-by-blow accounts of school matches which praise and criticize player performances with equal

candour.

School plays presented by the Dramatic Society and staged in the gym were an important part of school life in the early

1930s, and their public performances represented an important source of revenue for the School Sports Fund and Nick’s

favourite charity, the League of Mercy. At the end of the first term in 1932 three one-act plays were produced; in

early August staff and boys staged a very profitable performance of ‘Tilly of Bloomsbury', a romantic play adapted

from the popular book, ‘Happy-go-Lucky’ by Ian Hay. Mrs. Nicholson played the lead role of the unsophisticated but

charming shop-girl, Tilly, while Captain Nicholson played her ardent, upper-class admirer Dicky Mainwaring. The

production was not without accompanying off-stage drama: “On the afternoon of the first public performance Cox,

who was playing the part of Perce, was concussed in a bicycle accident, and his part was taken by Mr. Gillett, who

learned his part between tea and the performance.” The following year in April, no less than three staff couples,

the Nicholsons, the Forrests and the Astleys, joined with boys as cast members of a comedy, also by Ian Hay, called

‘The Middle Watch.’ This production, a tip-of-the-hat to Nick’s Navy background, was presented both at School and in

Nairobi’s Theatre Royal. (See a cast photo of ‘The Middle Watch’ later in this feature.)

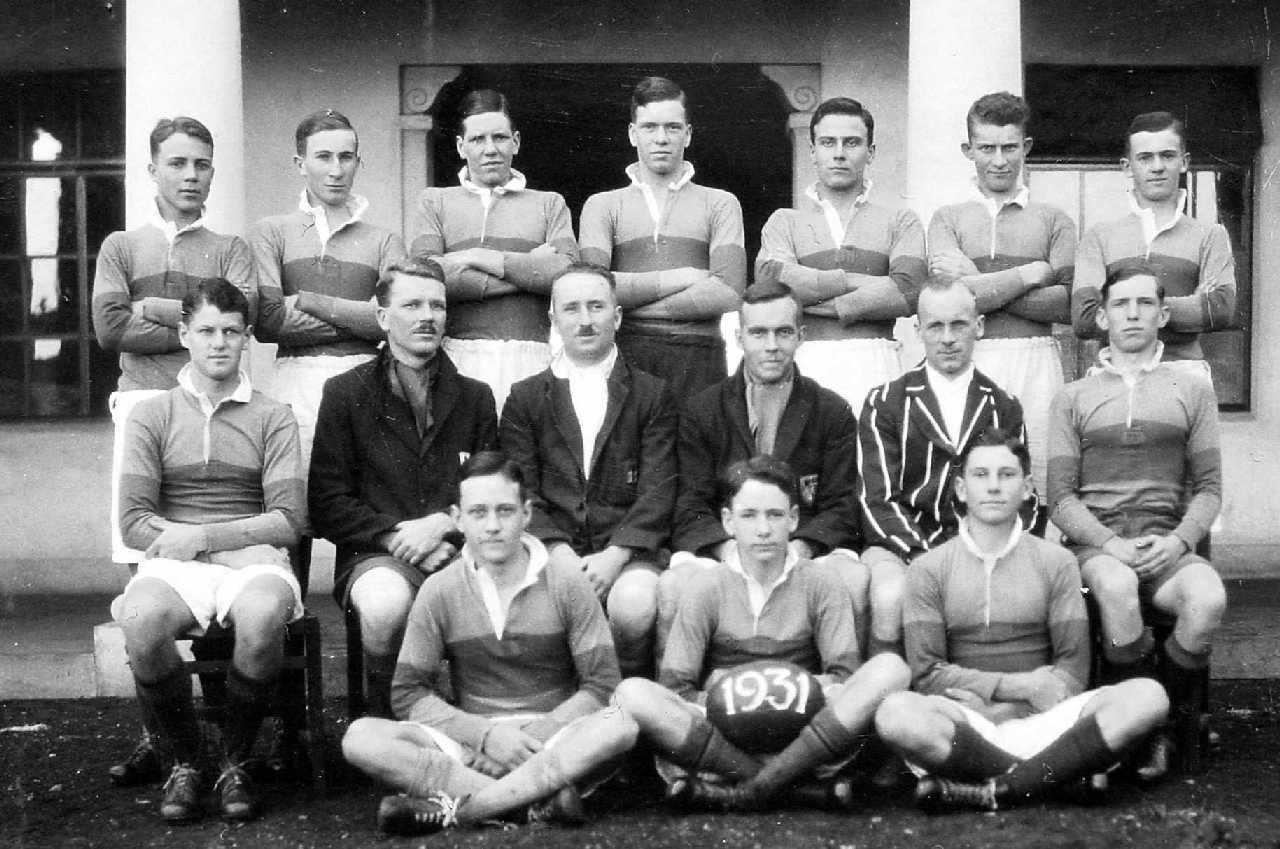

School Rugby Team 1931

Back row from left: (unknown), Douglas McDonald, J. Nimmo, (all others unknown).

Seated from left: (unknown), Bernard Astley, Jack Forrest, Rev. Jimmy Gillett, (unknown)

(Courtesy of Cynthia (née Astley) and Alastair McCrae)

These were the days when School sports teams featured masters among the players. Captain

Nicholson, already in his early fifties, was a vigorous rugby half for the Old Cambrians, a talented cricketer,

both in front of and behind the wicket, and a competitive cross-country runner. (Appropriately, the award for

cross-country was the Navy Cup, donated by Nick himself.) Of a rugby match between School and the Old Cambrians

on June 17, 1932 for example, it was reported that “the superiority of the Old Cambrians was due to their halves,

McDonald and Captain Nicholson.” (The McDonald referred to is Douglas McDonald, older brother of one of our

contributors to this feature, Angus McDonald – see below.)

In another match, this one at cricket against the Civil Service’s “A’ XI, “the School batted

extremely badly against very moderate bowling and lost nine wickets for 65 runs; however Captain Nicholson and Owen

Thomas came together for the last wicket and … batted on in the dusk until eventually Captain Nicholson was bowled

leaving the Service winners by 27 runs, but only after he and Owen Thomas had put on 74 for the last wicket. This

is a School record for a last-wicket stand.” And in review of the season as a whole, it is written that “altogether

last season’s cricket can be regarded with satisfaction, for when the strength of the fixture list is considered,

it was undoubtedly the most successful season the School has ever had.” (Earlier seasons include those when the boys

were in their old quarters at the Nairobi European School.) A great deal of the credit goes “to Captain

Nicholson’s wicket-keeping as shown by his stumping twenty-one people, while the School lost only ten wickets through

stumping (two of which Captain Nicholson himself stumped in one match in which his XI played against a boys’ XI), and

even more valuable testimony to his wicket-keeping is that the School scored 228 byes, while our opponents scored

only 114 – exactly half.”

1933 Boys Cricket XI

(Courtesy of Cynthia (née Astley) and Alastair McCrae)

Clearly, the values of competitiveness and playing field prowess, hallmarks of the public school

culture, were well established at Kabete by 1932, and no one exemplified them more energetically than the wiry, athletic,

and driven Captain Nicholson.

Captain Nicholson by Those Who Knew Him

at the Prince Of Wales School

Scouring school magazines for information is one thing; quite another is actually being able to

talk to former pupils from the Nicholson years. While we have been able to trace very few of them, our Webmaster,

Steve Le Feuvre (Clive 1970-75), managed to locate Old Cambrians Angus McDonald (Hawke, 1934-1937) and Frank Poppleton

(Clive, 1934-38), both of whom are in their eighties. In addition, David Watson, son of Claud Campbell Macdougall

Watson (1932-35), provided excerpts from his late father’s writings. It is a privilege to be able to present their

memories of Captain Nicholson.

Angus McDonald (Hawke, 1934-37)

“My first contact with Captain Nicholson was in his capacity as Headmaster of The Prince of Wales

School, Kabete, in January 1934, when I entered that school for my secondary education. I had known of him since 1931,

the year the school first opened as “Kabete School”, as my brother Douglas was among its first pupils brought over from

the old Nairobi School.

Although Capt. “Nick” (for such was the name by which he was fondly known) possessed no

academic qualifications, he was an outstanding administrator. He taught French very well, but apart from that,

devoted all his time to developing the school, particularly the grounds and playing fields. The basics were there,

i.e. level areas etc., but there was much still to be done, even in 1934, and we boarders were detailed once a week

in work-parties to do maintenance such as weeding, grass planting, and even tree planting.

“During my time, there were about 80 boarders only, and the boarding accommodation consisted

of four dormitory areas at first floor level, each denoted by a “Division No.”, following some sort of naval tradition,

I suppose. After breakfast on week-days, divisions were paraded along the quadrangle, each in the charge of a

House Captain, roll was called, and the Union Jack was hoisted with appropriate bugle calls. Captain Nick and

members of staff would be in attendance. The flag was lowered at 6 p.m. but with no ceremony other than “Last Post”

by the school bugler – however, everyone had to stand to attention irrespective of what they were doing – even in the

shower! One often heard instructions such as “close the starboard windows” or the use of other naval terms.

“I don’t think anyone ever feared Capt. Nick, but my Goodness they gave him full respect at all

times, staff included. One never heard a harsh word from him, but he was a strict fair disciplinarian, and was not

averse to caning, though he left the physical act to members of the staff or prefects. I recall one occasion when

he was really angry, though. A couple of lads asked permission to borrow the school bicycle in order to visit a sick

relative one Saturday afternoon. Not only were they seen by a member of staff at a cinema, but on the way back via St

Austin’s Mission (Convent) they failed to see that the road had been chained and crashed, badly damaging the bicycle!

This resulted in the whole school being assembled in the gym Monday morning, the misdemeanour announced, and each given

six strokes by the Head Prefect in front of the assembled boys!

“Capt. Nick was very keen on sport, particularly cricket, in which he was coach and wicket-keeper

for the school’s 1st XI. The Oval was his pet, and he had each boy plant a tree round the field on the occasion of King

George V’s Jubilee. He would often do a bit of coaching, and demonstrate the art of watching the ball by offering a

“simuni” (a half shilling) to any one who could bowl him, using a cut down narrow bat. Another of his favourite

pastimes was cross-country running, and so, inevitably, we boys had to run up the valley to the Veterinary Labs and back

several times during a term. It was nothing for Capt. Nick, at age 55 plus, to don shorts and ‘tackies’ and go for a

five-mile run at 6 a.m. accompanied by his Scottish Terrier, Jock. Remembering that those years were in the depth of

the Depression, government money was hard to come by for sports equipment, and on more than one occasion Nick would use

his own funds. A specific item was a fair-sized ‘sit on’ motor mower and roller, which was essential for the rather

large grounds.

Empire day 1937 in the Quad with Captain Nicholson in full Naval Uniform

(Courtesy of Oliver Keeble from the collection of his father, O.J. Keeble, Hawke, 1934-39)

“He was a devout Christian, and I suppose like many other similar institutions, we had Grace

said at all meals, Morning and Evening prayers each day, and Morning and Evening services on Sundays. These were mostly

conducted by Rev. Jimmy Gillett of the staff. So too, was he a devoted Monarchist and protagonist of the British

Empire – insisting on pomp and ceremony on Empire Day, with march-past by the OTC, and he in full regalia of a Naval

Captain. 1935 being the year of the King’s Silver Jubilee, Nick tried his hand at stage directing, and the school

staged a play called “Oliver Cromwell” at the Theatre Royal in Nairobi.

“As far as I could tell, he was in good standing with the Department of Education, and he appeared

to be on good terms with the Governor and senior government officials and also with leaders in the community. Mrs.

Nicholson was a delightful person, and it was considered a treat to be detailed off to help in her little garden, as

this entitled one to tea and hot scones with her in her quarters. She would help in such matters as school plays etc.

but otherwise was never seen to be involved in matters that did not concern her. When the school opened in 1931, the

houses Hawke, Rhodes and Clive were brought over from Nairobi School, but I believe it was Capt. Nick’s idea that a

fourth house be created and named after the then Governor, Sir Edward Grigg.

“He always had in mind the welfare of his pupils, who came from all walks of life. He was a

discerning selector of leaders to become prefects, and made use of their talents. He would often refer to them as his

Petty Officers.

“In my time there was one boy, McClelland by name, who was a prefect and thought much of by Capt.

Nick. (John McClelland entered the school in 1933.) McClelland was attacked by Rheumatic Fever (I think) and died.

I never saw a man so upset as was Nick. He had a bronze plaque in his memory attached to the wall in the cloisters.

I wonder if it remains? It is such a pity that Capt. Nick and his wife were childless.

Seventy-two years later, the McClelland memorial plaque is still to be found

in the temple or rotunda midway along the

west wall of the quad’s cloisters.

(Photo commissioned by Webmaster, Steve Le Feuvre, and taken in January 2006 during a

visit

to the school by James Ilako and Abed Malik............all of whom are formerly of Clive House, 1970-75).

Photo taken by

Ailish Byrne.

“In the early days,” Angus continues, “Nick had an old Riley car, and one of the older boys,

whose name I forget, was old enough to have a driving license (16 in those days), and this chap was used as a driver on

many occasions to execute orders. After he left, Nick acquired a Ford V-8 box-body.

“I don’t remember when he retired, but imagine it was probably in the same year that I left,

and I lost complete track of him. I did hear that in England he had blinded one eye when a chip from a log that he was

cutting with an axe flew up and hit his eye. I do not even know when he died. There wasn’t a single boy that I knew

who would refer to Capt. Nick in other than the most endearing and respectful terms. It was certainly a happy and proud

school."

Frank Poppleton (Clive, 1934-38)

“Capt Nicholson was always known as Nick. I was very young and a new comer to the school and

remember that he was outstanding as a person and a character. He was greatly admired and respected by students and

staff, and was reputed to have been a Naval Captain and had two ships sunk under him in the Great War.

“I recall that many of the rules and regulations prevailing at the school were of Naval

origin - the school was divided into divisions; the raising and lowering of the flag; reveille and retreat.

“The bicycle incident (referred to by Angus McDonald) and the subsequent flogging are clear

in my mind; one of the boys was called Webster.

“I also remember McClelland. He suffered from terrible cramps and had to be attended to in the

dormitory at night. On leaving school he joined the EA mountain artillery and was killed by the Italians in Somaliland

in the EA Campaign. (Frank is referring to John McClelland’s younger brother David who entered the school in 1936 and

who died in action on August 15 1940.)

“I wish to thank you for renewing my contact with Capt Nicholson and the Prince of Wales

School; this was a very important part of my life and I appreciate being reminded of those days.”

Claud Campbell Macdougall Watson (1932-35)

“I was soon introduced to my new school which was at Kabete, a few miles north of Nairobi. I used

to cycle there, part of the way along native paths until I joined the main road north further west. I enjoyed this cycle

ride so much that I used to dream about it years later. Cycling along the Kabete road itself was a dreadful experience.

Like most roads in those days it was a dirt road not surfaced with macadam. This gave it a horrible corrugated surface

which was jolting to ride on. In a car if you travel fast enough you could skate along on the top of the corrugations;

but it must have been a terrible strain on the springs. In wet weather the dirt turned into mud.

“The Prince of Wales school had been designed by a famous architect, Sir Herbert Baker, who had

also designed many famous buildings in India. It was cool and spacious and the classrooms never felt hot and stuffy,

even in the hottest weather. This is a great asset when living in the tropics at a time when luxuries such as air

conditioning were unheard of.

“The headmaster was a Captain Nicholson, an ex-naval officer who ran the school like a ship.

There were bugle blowing rituals morning and evening with the Union Jack being raised and lowered. He was a real

gentleman who could be a strict disciplinarian but whose decisions were always fair ones. He was thus greatly respected

by all the boys under his care. They were very much a mixed bag: mostly Europeans, but with a large number of Boer Dutch

whose parents had emigrated to Kenya and taken up farming. The two races mixed quite well but it needed a good headmaster

to keep good order. The Dutch boys were good at outdoor sports but inclined to be quarrelsome, and many an argument began

because of some adverse comment about the Boer war, which to them was very recent history, even if to us British boys

it was something in the remote past.

“I had to study for the dreaded School Certificate again; but to my delight I found that the

French teacher was Captain Nicholson himself. He was not a trained teacher but had taught at Dartmouth. He spoke fluent

French and was the first teacher of the language I had ever found any good. He really made the language alive and

interesting, and when I sat the exam the following summer I had no difficulty passing the third time.”

“Captain Nicholson goes on leave 31 March 1934”. The person shown on top

of the DH66 aircraft is

either the pilot or a member of the ground crew. Normal time for the journey by air was eight days.

(Courtesy of Cynthia (née Astley) and Alastair McCrae)

On the Staff side, several teachers who served under Captain Nicholson, and all of whom have

long since passed away, wrote tributes to the memory of their old headmaster at the time of his death in 1958. Their

memories, published in that year’s Impala and reproduced below, provide new details about the man, his personality quirks,

and his leadership style. Together with the former schoolboy memoirs quoted above, they provide a unique glimpse of the

essential Captain Nick as seen through the eyes of ‘officers and ratings’ who served with him at Kabete.

Mr. B.T. Lindahl (Staff)

“Capt. Nicholson came to Kenya in 1925 after a distinguished naval career and brilliant service in

the First World War. He had been invited to join the Education Department by Sir Edward Denham, who had selected him for

the post of first headmaster of the projected Boys' Secondary School which was to be built at Kabete. He had to wait over

five years before the school was completed and during this period he was headmaster of the old Nairobi European School,

and it was not until the beginning of 1931 that the move to the new building took place and this school was founded. Capt.

Nicholson had a formidable task ahead of him. He was to start the first real boys' secondary school in the colony and it

was pioneer work indeed. There were no traditions to build upon. These he had to found himself. The school had no past

history or record of achievement to inspire its members, but it had an enthusiastic headmaster and staff. Materially it

had a fine building surrounded by a piece of virgin Africa and builder's rubble and Capt. Nicholson set to work to lay out

the grounds as you know them today. Every afternoon schoolboys were detailed into working parties and, with the masters on

duty, dug, cleared and planted. In these parties the most energetic worker was always Capt. Nicholson. Soon the grounds

took shape, playing fields were laid out, the jacaranda avenue along the main drive, as well as shrubs, hedges and trees

were planted and Mrs. Nicholson laid out and planted the flower beds, which were to remain her special responsibility for

the rest of the Nicholsons' stay at the school.

Hard at it with jembes, laying out the grounds at Kabete in 1931

(Courtesy of Cynthia (née Astley) and Alastair McCrae)

“The strongest and most lasting impression one has of Capt. Nicholson is his unbounded energy and

devotion to duty. He set himself and expected of others immensely high standards of honour and personal conduct and of

reverence for all that was good and true. The school was his life. It was his work and his recreation. He never let up.

He had a teaching time-table nearly as full as that of any assistant master, took cricket practices almost every afternoon

and ran the administrative side of the school with the help of only a single typist. At night when one was ready to go to

bed and chanced to look out across the quadrangle one would see the light still on in his office and yet he would be up

before anyone else in the morning, very probably taking a cross-country run before breakfast. He worked hard and expected

his staff to do the same, but he was always deeply appreciative of all one did. It was his great human qualities and his

concern for the welfare of his staff and pupils that endeared him to everyone. His and his wife's hospitality and

generosity will always be remembered by those who were privileged to know them and they entertained all who were connected

with the school generously and often.

“Capt. Nicholson's two passions, besides work, were cricket and the theatre, but it was always

school cricket and school plays that absorbed his energies. In those days the school was only a fraction of the size that

it is today, but the School Cricket XI, coached by Capt. Nicholson, was a team to be reckoned with in adult sports circles.

Many people in Nairobi will still remember the excellent plays which he produced and which incidentally provided much

needed revenue for the School Fund. You who today enjoy swimming in the magnificent school bath might be interested to

hear that it was Capt. Nicholson who, twenty-four years ago, organized the Swimming Bath Fund and started it off with a

generous personal donation. Few people know the extent to which he contributed to school expenses. If he felt that

something was required for the well-being of the school and Government was unable to provide the necessary funds, he

immediately put his hands into his own pocket. When he retired he asked that any money which had been collected for a

personal presentation to him should be put towards a fund for building a new cricket pavilion.

“The school was still in its infancy when he retired in 1937 but in the six years of its life it

had earned a reputation throughout East Africa. It had a fine tradition and an excellent record both academically and in

the field of sport. Since then it has grown and progressed enormously under successive splendid headmasters — I exclude

from this generalization my own short spell as headmaster during the evacuation to Naivasha — but I hope it will never be

forgotten that the foundations of its fame and traditions were laid by Bertram Nicholson and there can be few among those

who came into contact with him who have failed to be permanently inspired by his enthusiasm, his devotion to duty, his

tradition of unselfish service, self-discipline, respect for authority and national pride."

Rev R.H. Barton (Staff)

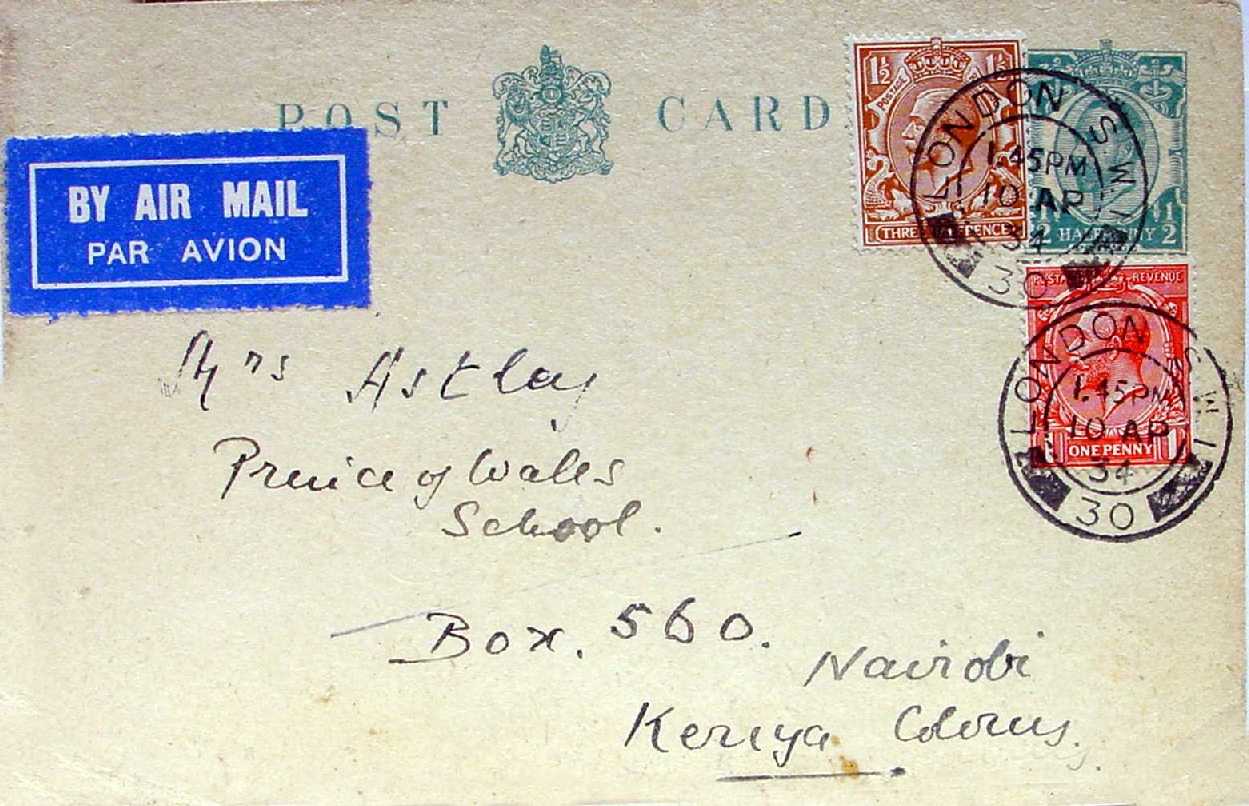

“Recently I found a postcard I wrote to my mother in March 1928. It said "I have had an interview

with the Headmaster of the European School, Nairobi. I liked him immensely." That first impression never changed in

30 years, except that the liking grew into admiration and love. I joined the staff of the Nairobi School in January

1929, was transferred up-country in September 1930, but succeeded in rejoining Capt. Nicholson at the Prince of Wales

in January 1936. By that time the teething troubles of the School were over, and was I ever thankful! I never fancied

myself with a jembe. Larby, Forrest, Henry Gledhill, James and others bore the heat and burden of the day, and the pace

was hot. But I remember the bitterly cold day when we watched Sir Edward Grigg lay the foundation stone on a barren

expanse of wind-swept grass, and then the desert blossomed like a rose under the direction of Capt. and Mrs. Nicholson

and to the accompaniment of mighty grumbling from everybody else, boys and staff. But Nick worked harder than anyone,

and you could not let him down.

“He seemed so old to us youngsters (he was 52 in 1931) but his energy was terrific. A wonderful

spirit dwelt in that small frame -- he was built on the lines of Nelson and Jellicoe -- and he kept himself absolutely

fit. At Nairobi he played fly-half in "tackies" in school rugby practices; we used to play 40 minutes in the first half

and then until it was dark. Cricket he loved even more: he was a good batsman and a fine wicket-keeper, and when he

stopped playing for the school, he helped to start the Wanderers' Club. He broke his arm in one match on the old Police

ground near the Norfolk while batting; we took him up to the hospital where it was set, he walked back to the ground,

finished his innings and fielded at cover-point with his arm in a sling. No headmaster has ever run in the Cross Country

since he did.

“Captain Nicholson was a real Christian with the deep and simple faith of a sailor: he had seen

God's wonders in the deep, as he told the School one day at prayers when he recounted his rescue from the sea after the

sinking of the `Cressy'. He carried his faith into his daily life, and his character was founded on his beliefs. There

was nothing mean or petty about him; he had no pride; he was as honest and straight-forward as the day, and generous to a

fault. He was our headmaster not so much by right as by example; we did our best to follow him and when he retired, we

continued on the lines that he had set for us.

Empire Day 1937, with Capt. Nick in the background. In that year the Cadet Corps was recognized as

a contingent of the Officer Training Corps and was affiliated with the Kenya Regiment.

(1952 Impala, courtesy of Martin Langley, Nicholson, 1956-61 and the Impala Project)

“He was a grand patriot with a love of ceremony such as the sounding of Retreat which he began.

He had eaten the King's salt like Wellington and he would always serve him. Empire Day was almost a religious festival

to him. Sometimes his love of England got him into trouble: the quotations he had painted round the Nairobi School hall

aroused the wrath of Scots and the contempt of Julian Huxley. But for him life must consist of service. "Fear God,

honour the King" without a thought of self. It was not a bad creed for a young country.

“I doubt whether he was a good headmaster from a professional viewpoint. He always expected

everyone to volunteer, and the rule he laid down for his staff in 1931 nearly caused a mutiny. In bed every night at

10 p.m.? They called it a battleship, not a school. He was said to dislike women — what a time he must have had in the

old mixed school, and how Miss Kerby must have battled with him! And he expected all his staff to remain bachelors.

He was not at all pleased when I arrived with a wife. All washing had to be hung down by the railway line. But his

bark was worse than his bite and his own married life was unalloyed happiness. Mrs. Nicholson was as active as he was

and a wonderful support to him. The girls his staff insisted on marrying loved him just as much as their husbands did.

He was a most charming and lovable man, and those blue eyes with crinkles round when he smiled were devastating. But

women on the staff? Not if he could help it, and he preferred to buckle down to his French and to teach it himself.

He set the tradition whereby the headmaster of the Prince of Wales does more teaching than any other headmaster.

Cast of the 1933 school play, ‘The Middle Watch.’ Back row: Captain Nicholson, second from

left; Jack Forrest in the middle; and Bernard Astley, second from the right. Middle row: Mrs.

Astley, second from the right; Mrs. Nicholson at far right. Mrs. Forrest is believed to be one of the

other ladies in the picture. (Courtesy of Cynthia (née Astley) and Alastair McCrae)

“He had a passion for stage productions. They did not make much money and they made an awful lot

of work for everybody, but it was great fun. "A Kiss for Cinderella," "The Middle Watch," "The Dogs of Devon,"

"The Adventurers"; they all showed his imagination, his patriotism and his love of ceremonial.

“He may not have been a very good headmaster, but he and his work live on in the buildings

and the playing fields, the spirit and the traditions of the school. He was very beloved and a great headmaster.”

Colonel J.R. Forrest and Mr. N.B. Larby, Esq., O.B.E. (Staff)

“Captain Nicholson's service in Kenya, as in everything he did, had one remarkable characteristic —

a singleness of purpose which ran common in all his many qualities. His very deep devotion to the school and its pupils

over-rode all other considerations and inspired the achievements on which its traditions have been so firmly built by

his successors. In this his work drew much strength from his deep and simple religious faith and a sincere belief in the

value of prayer which guided him throughout his life; with this went an unflinching patriotism to his country and to his

conception of the Commonwealth.

School Cricket Team 1936

Staff members, seated from left: E.H.C. "Nyoka" Luckham, Norman "Bull" Larby, Captain

Nicholson and "Ginger" Gledhill. (Courtesy of Gerald Rosenthal and Heather (née Arderne)

Rosenthal whose father, “Archie” Arderne, is shown second from the right in the back row.

“His extraordinary capacity for work was made possible by this intense moral fervour in everything

he undertook together with an equally intense belief in physical fitness. He was rather slightly built and this gave no